The Timeless Beauty: A Comprehensive History of Islamic Art and Calligraphy

Introduction: Where Faith Meets Aesthetics

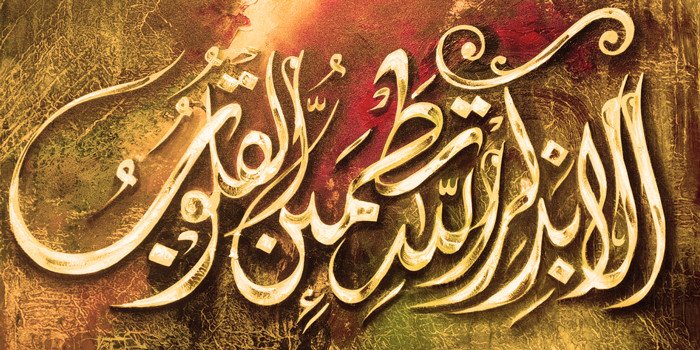

Islamic art and calligraphy are among the most revered and recognizable forms of artistic expression in the world. Rooted in spirituality, these art forms developed not just to beautify, but to convey divine messages and cultural identity. From the walls of mosques adorned with elegant Thuluth scripts to ancient manuscripts illuminated with geometric patterns, Islamic art has evolved into a rich tapestry of form, function, and faith.

This blog dives deep into the history of Islamic art and calligraphy, tracing its development from the 7th century to the modern era and exploring the cultural, religious, and artistic impact it has left across civilizations.

1. The Origins: Islamic Art in the Early Centuries (7th–10th Century)

Islamic art began to emerge in the Arabian Peninsula shortly after the revelation of the Quran in the 7th century. Early Islamic art avoided figurative representation, focusing instead on abstract patterns and script to reflect the monotheistic nature of Islam.

Key Characteristics:

-

Aniconism: Avoidance of human and animal figures in religious contexts.

-

Geometric and floral motifs: Used as infinite patterns to symbolize the eternal nature of God.

-

Kufic script: The earliest form of Arabic calligraphy, characterized by angular and linear shapes, often used in Qurans and architectural elements.

During the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphates, Islamic art began to flourish with the construction of mosques, palaces, and madrasas decorated with inscriptions and tile work.

2. The Golden Age: Expansion and Innovation (10th–15th Century)

The Islamic Golden Age (roughly 8th–13th century) saw not only a boom in science and philosophy but also in art and calligraphy.

Artistic Developments:

-

Illuminated manuscripts: Intricately decorated Qurans and literary texts flourished in Persia, Andalusia, and the Ottoman Empire.

-

New scripts: Introduction of Naskh, Thuluth, and Muhaqqaq scripts allowed greater artistic flexibility and beauty.

-

Architecture: The Alhambra (Spain), Dome of the Rock (Jerusalem), and Sultan Hassan Mosque (Cairo) became masterpieces of integrated calligraphy and design.

In this period, calligraphy wasn’t just a written form; it became a core visual language of the Islamic world.

3. Regional Styles and Influences

As Islam spread from Spain to Southeast Asia, its art and calligraphy absorbed local traditions while preserving Islamic ideals. This created a wide spectrum of regional styles.

Ottoman Empire (Turkey):

-

Developed the Diwani and Tughra scripts.

-

Mastered Iznik tilework, blending calligraphy with colorful arabesque patterns.

Persian Art:

-

Renowned for Nastaʿlīq script, considered one of the most fluid and aesthetically pleasing styles.

-

Combined poetic verses with miniature painting.

Maghribi Style (North Africa):

-

A distinctive cursive form with exaggerated curves.

-

Used mainly in Maghreb Qurans and manuscripts.

Mughal India:

-

Blended Persian and Indian influences.

-

Calligraphy adorned palaces, including the Taj Mahal.

Andalusia (Spain):

-

Rich in arabesques and geometric art.

-

The Alhambra showcases Quranic verses etched into walls with floral elegance.

4. Symbolism and Spiritual Significance

Islamic calligraphy goes beyond aesthetics; it is deeply spiritual and symbolic. Because of the Quran’s sacred nature, the written word is a direct reflection of the divine.

Key Concepts:

-

Tawhid (Oneness of God): Represented through repeating symmetrical patterns and endless designs.

-

The Quran as Divine Word: Every stroke is considered an act of devotion, turning the scribe into a spiritual practitioner.

-

Sacred Geometry: Employed to depict the perfection of God’s creation.

Thus, Islamic art isn’t just decoration—it’s a visual dhikr (remembrance of God).

5. The Calligrapher’s Role in Society

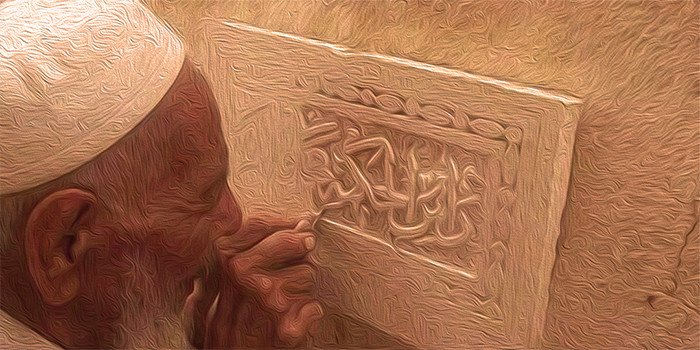

Throughout Islamic history, calligraphers held esteemed positions, especially in courts and religious institutions.

Training and Discipline:

-

Mastery often took years of apprenticeship under a “ustad” (master).

-

Practice required patience, humility, and spiritual focus.

-

Tools like the reed pen (qalam) and special ink were chosen with ritual-like care.

A calligrapher’s work was more than artistic; it was an offering of faith.

6. Decorative Applications of Islamic Calligraphy

Islamic calligraphy transcended paper and appeared across various mediums:

Architecture:

-

Quranic inscriptions adorned mosques, domes, minarets, and doorways.

-

Thuluth script was often used in monumental architecture.

Ceramics and Pottery:

-

Bowls, plates, and tiles carried poetic or religious inscriptions.

Textiles:

-

Calligraphy embroidered on robes, prayer rugs, and wall hangings.

Metalwork:

-

Swords, lamps, and utensils were engraved with verses and names of Allah.

In each form, calligraphy served both as decoration and devotion.

7. Transition to the Modern Era (19th–20th Century)

With the advent of printing and colonial influence, traditional Islamic art faced challenges, but it never disappeared.

Modern Influences:

-

Western art movements introduced new perspectives.

-

Artists began blending calligraphy with abstract art.

-

Political and social messages started appearing in calligraphic compositions.

Figures like Hassan Massoudy and Nja Mahdaoui brought calligraphy into the world of contemporary art, exploring identity, freedom, and faith through the written form.

8. Digital Islamic Art and Calligraphy Today

In the 21st century, Islamic calligraphy has embraced technology.

Current Trends:

-

Digital brushes and vectorization allow artists to create scalable, editable calligraphy.

-

NFTs and online galleries open new platforms for exposure and sales.

-

Augmented Reality (AR) and interactive Quran apps integrate calligraphy in immersive ways.

Modern calligraphers now combine traditional tools like the qalam with iPads and styluses, merging past and future seamlessly.

9. Preserving and Teaching the Tradition

Efforts are underway globally to preserve Islamic art and calligraphy:

-

Workshops and Institutes: Places like the Prince's School of Traditional Arts and Istanbul’s IRCICA train new generations.

-

Online courses and YouTube channels provide access to calligraphy instruction for global learners.

-

UNESCO Heritage Status: Several Islamic calligraphy traditions have been recognized as intangible cultural heritage.

The tradition is not only alive but thriving—with deeper global appreciation than ever before.

Conclusion: A Legacy Written in Beauty

The history of Islamic art and calligraphy is a journey through faith, culture, and creativity. What began as a sacred means of preserving the Quran evolved into one of the most enduring and admired art forms in the world. It transcends borders, languages, and centuries—offering a visual language of harmony, rhythm, and divine beauty.

Today, as artists continue to innovate while preserving classical techniques, Islamic art remains not just a heritage of the past, but a living, evolving tradition for the future.